A Flurry of Plurry Slurry

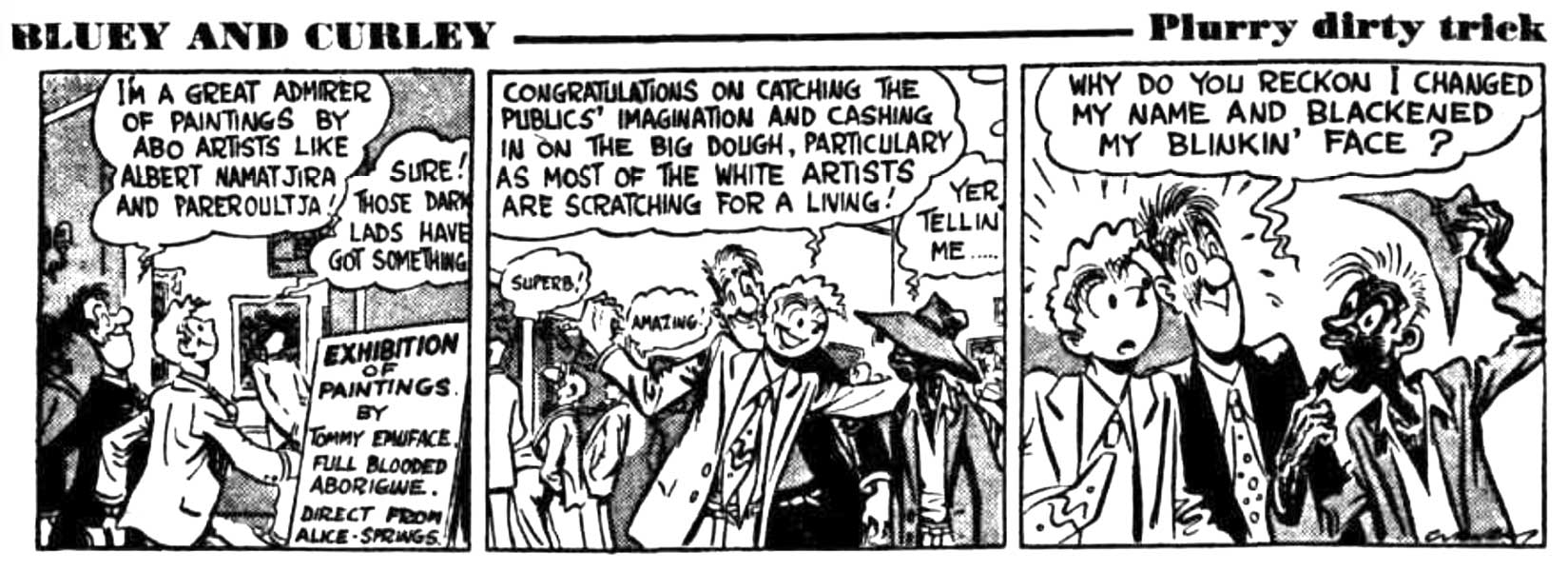

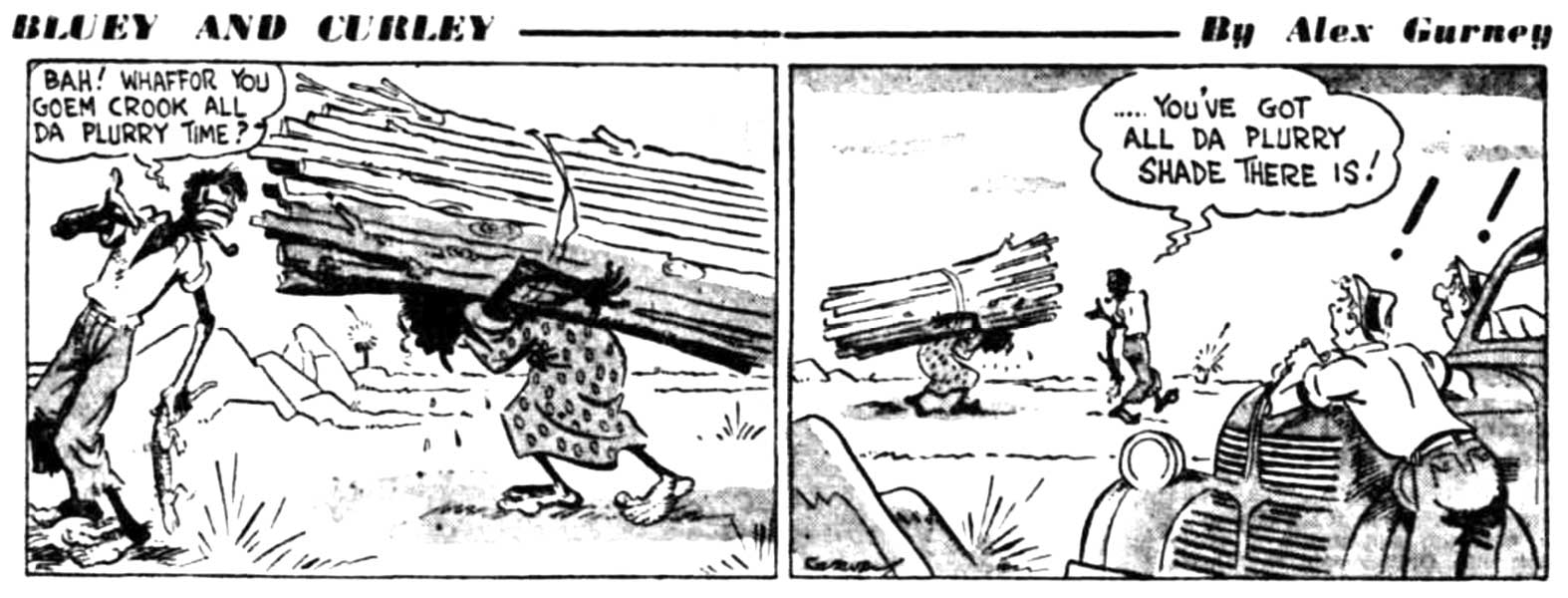

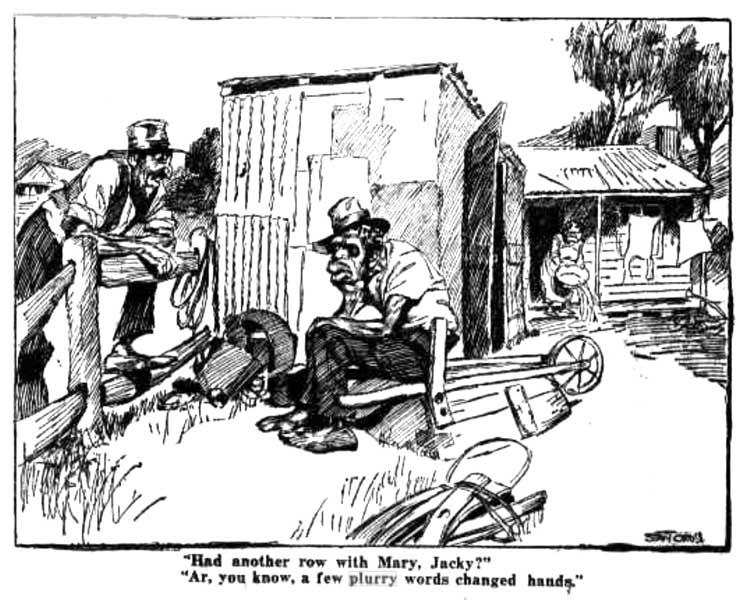

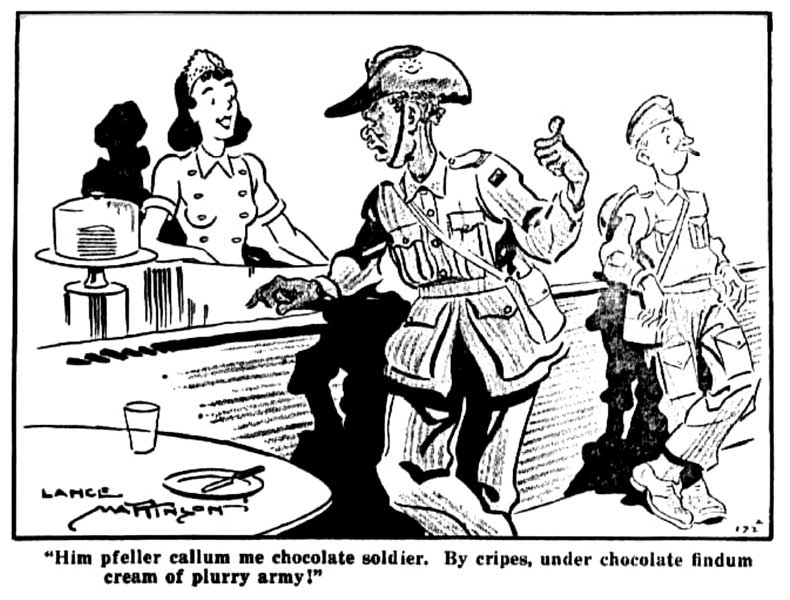

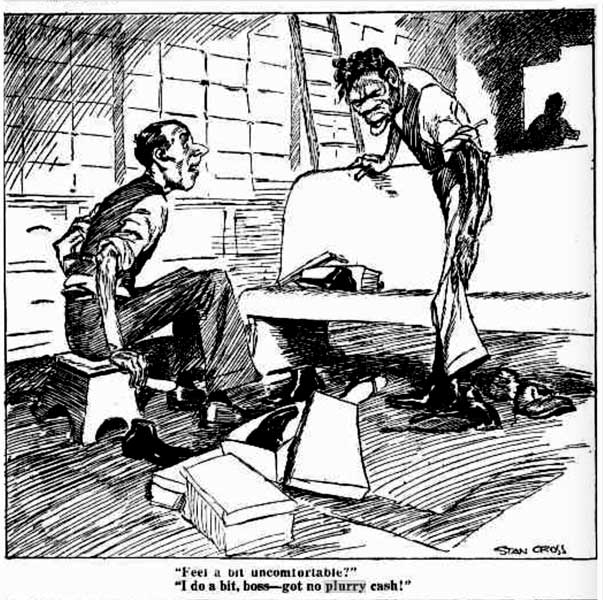

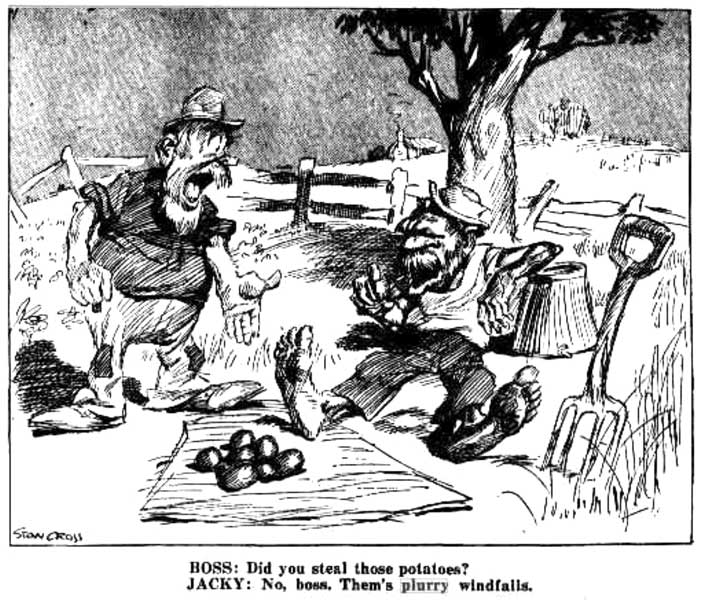

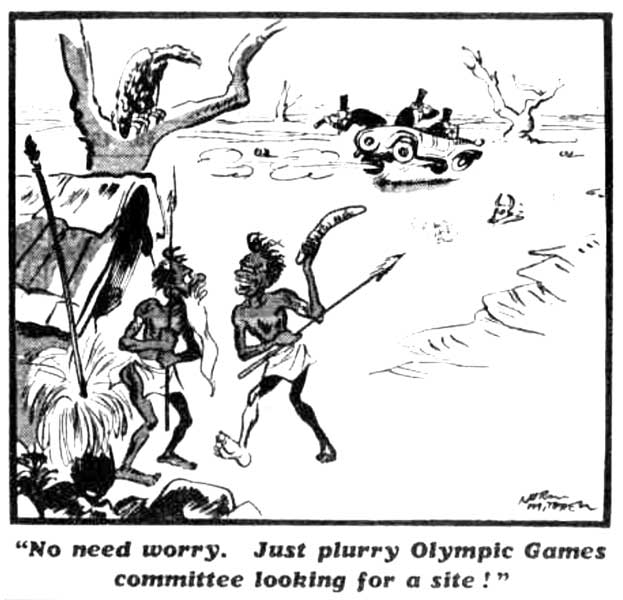

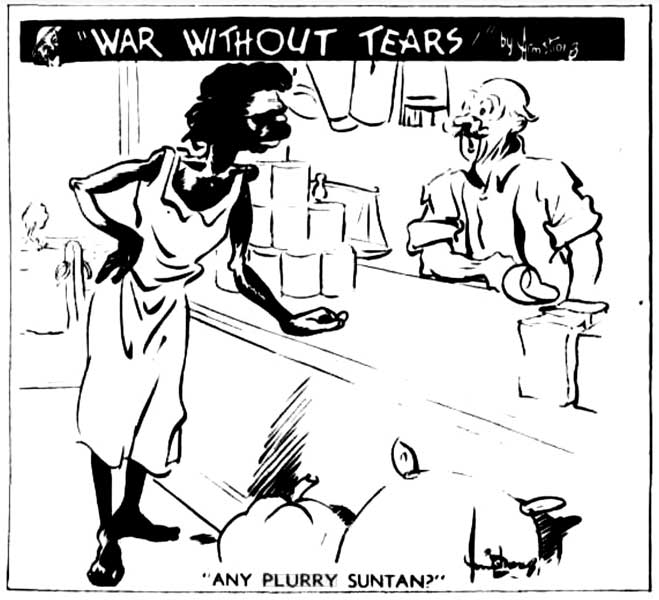

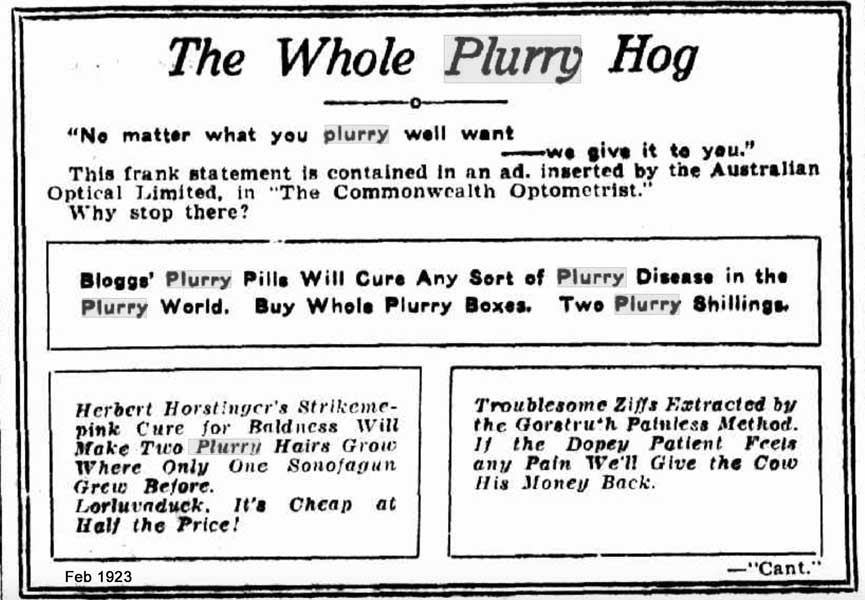

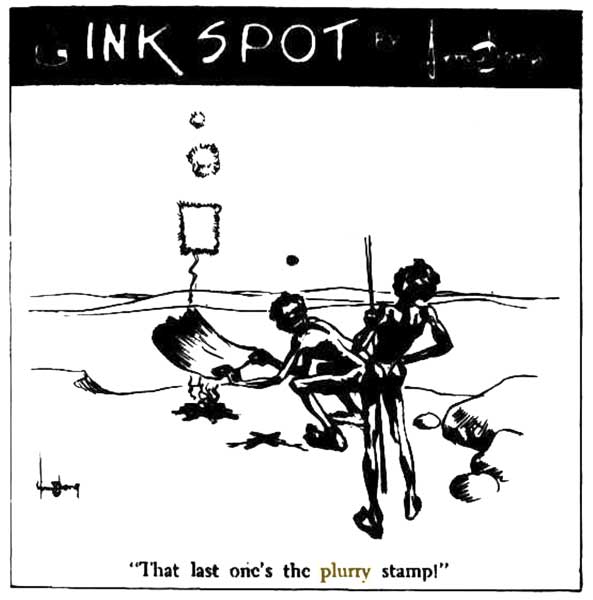

My old man didn’t swear much and the only cussing I ever really heard from him when I was a youngster was the adjective /adverb ‘Plurry’. This piece of (now outdated) Australian slang is supposed to have its origin in the mispronunciation of the word ‘bloody’ by Australia’s indigenous population. According to the Oxford Dictionary ‘plurry’ is used to express anger, annoyance, or shock, or simply for emphasis. What follows are a selection of examples from early newspapers: I was re-shocked to discover just how cruelly demeaning, dismissively racist and sexist white Australians were /are. The terms ‘darky’ and ‘nigger’ were frequently used and indigenous people consistently portrayed as lazy, drunken and /or stupid. I have never heard of our indigenous people using smoke signals – a false custom frequently employed to denigrate in many cartoons. About the only positive indigenous attribute portrayed by our blinkered plurry forebears is a plurry great sense of plurry humour. Plurry bastards!

‘NO PLURRY — ‘ ‘

So disgusted with the dry weather, the heat waves, and the dust storms, is the Editor of the Junee paper that he suggests that the country shouId be handed back to the blacks with a card inscribed: ‘No Plurry Good.’

That reminds the Editor of the ‘Spectator’ of an incident that took place in Tumut when he was resident there, viz:

A blackfellow, overhearing as remark that Australia should be handed back to his race, chipped in with the answer:

No fear, you took it from us and made a plurry mess of it; we don’t want it.

Hillston Spectator and Lachlan River Advertiser (NSW : 1898 – 1952), Thursday 21 December 1944, page 4

“Plurry — Cockey”

“Coolah” writes: In a western pub there is an aged cockatoo perched in the bar, and he is an accomplished conversationalist, in fact the only way of keeping him out of an argument is to shift him and the portable perch out to the stable yard. He feels this keenly and will sulk for hours. One morning a half-caste, loafing about the town, was commanded to escort him into exile, and though he sympathised deeply and volubly with the bird, he couldn’t get an appreciative word out of him.

Think yer too plurry proud to speak to a fellow what ain’t quite white do yer. You an’ yer tin stump, yer blanky upstart. Why, I knew yer father an’ mother, an’ yer whole dashed family when yer lived in a gum tree.

Gundagai Independent (NSW : 1928 – 1939), Monday 24 November 1930, page 4

During August, 1938, when Hutton was making his Test record 364 at Kennington Oval, Australian cattlemen in the faraway Kimberleys (that part of North-Western Australia from which Chips Rafferty and his “Overlanders” began their trans-continental journey), were listening in on their pedal wireless set to the Test, broadcast in the small dark hours of the morning. An aborigine, whose curiosity was aroused, listened with them. When Hutton at last passed his 300 mark his black eyes widened with amazement – “Blimey!” he exclaimed, “How many this plurry fella make in daylight?”

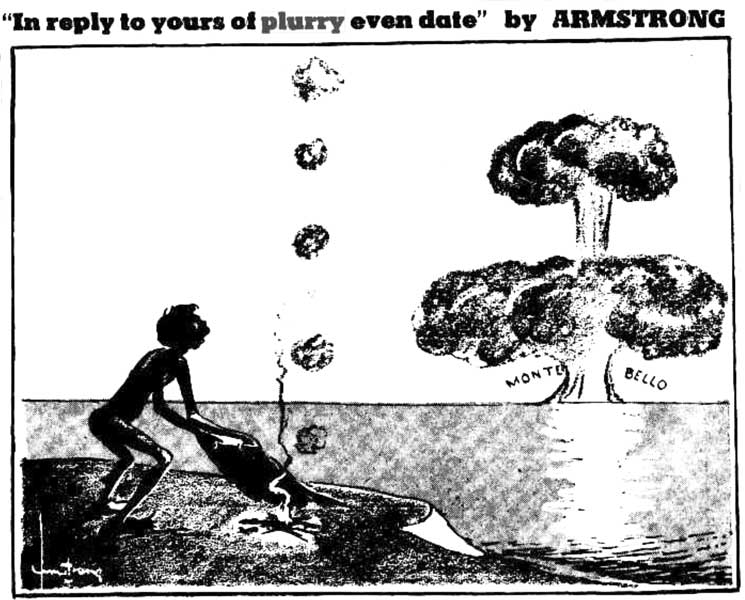

Brisbane Telegraph (Qld. : 1948 – 1954), Wednesday 28 June 1950, page 36

“TOO PLURRY SCARCE”

“TOO PLURRY SCARCE”

Down at a buckjumping show at Gloucester the other night the show people were trying to get someone to ride the wild bullock. Just then, along ambled young Albert Cook, one of the offspring of the abo. sons of the soil, and a descendant of the mightiest horseman in the district. “Hey, Alby,” was the shouted chorus. ‘Come on, Alby, give him a go.” But Alby shook his head and winked wisely.

No, he said. Some of youse white blokes have a go. Blackfellows gettin’ too plurry scarce about here.

Armidale Express and New England General Advertiser (NSW : 1856 – 1861; 1863 – 1889; 1891 – 1954), Friday 2 December 1927, page 5

“Took Our Plurry Country,” Says Binghi

NEWCASTLE Sunday

JACKIE BUNDABUNGA, a full-blooded aborigine from Botany Bay had a lively “pow-wow” with Newcastle railway officials at the weekend. Failing to produce the voucher for a free rail ticket to  Sydney he became sarcastic.

Sydney he became sarcastic.

You took our plurry country, and now not gib it a train ride, he said.

However, Jackie proved an adroit ”nip.” After several small coins had been transferred to the pocket of his tattered coat, he borrowed a couplet of brush box leaves from the floral decorations of the refreshment room and regaled his audience with snatches of “Pal o’ Mine” and “When it’s Moonlight on the Rockies”. Then, with a cheery “hooray,” he headed, per foot, along the road to La Perouse.

Labor Daily (Sydney, NSW : 1924 – 1938), Monday 14 March 1932, page 1

NINE MILES FROM GUNDAGAI

I CAN’T FORGIVE THAT PLURRY DOG

I’m used to punchin’ bullock teams

Across the hills and plains,

I’ve teamed out back this forty years

In blastin’ droughts and rains.

I’ve lived a heap o’ troubles down

Without a bloomin’ lie

But I can’t forget what happened me

Nine miles from Gundagai.

It was gettin’ dark, the team got bogged

Th’ axle snapped in two,

I lost me matches and me pipe

So what was I to do?

The rain came on, ’twas bitter cold,

And hungry too was I,

And the dorg he sat in the tucker box

Nine miles from Gundagai.

Some blokes I knows ‘as stacks o’ luck

No matter ‘ow they fall,

But there was I, “Lor’ luv a duck!”

No blessed luck at all.

I couldn’t make a pot o’ tea

Nor get me trousers dry,

And the dorg sit in the tucker box

Nine miles from Gundagai.

I can fergive the blinkin’ team,

1 can fergive th’ rain,

I can fergive the dark and cold

And go through it again.

I can fergive me rotten luck.

But hang me till I die

I can’t fergive that plurry dorg

Nine miles from Gundagai.

West Wyalong Advocate (NSW : 1928 – 1954), Monday 19 October 1942, page 1

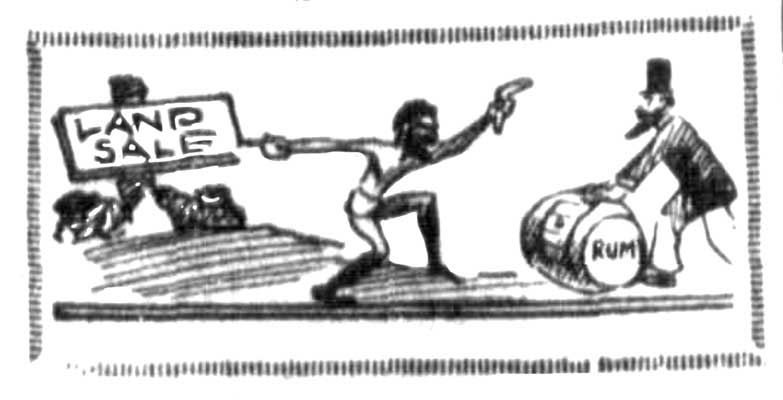

King Billy, of the Macleay River, N.S.W., now deceased, upon being asked what he most liked in all the world replied:

Oh glassa rum, my word!

Now suppose you had the rum what else would you like?

Bit bacca. I think.

Being further interrogated as to what desire he would next wish to gratify, Billy scratched his head and replied:

Nuther glassa rum my plurry word.

Port Pirie Standard and Barrier Advertiser (SA : 1889 – 1898), Thursday 8 October 1891, page 4