My maternal great grandfather, Alexander Migan, was born in 1873 on Waiheke island. Waiheke is in the Hauraki Gulf, not far from Auckland on the North Island of New Zealand. In the 1870′s, three decades after the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand’s two main islands were like two different countries. The 1860s had been a turbulent decade. Much of the North Island had been ravaged by the New Zealand wars. Māori still dominated most of the interior of the North Island. New Zealand was a maritime frontier, especially in the north – a string of coastal enclaves connected by sailing ships, small steamers and waka (canoes); or by rough tracks and roads hacked through dense bush, travellers on which had to cross dangerous fast-flowing rivers. When Alex was a youngster, most people travelling any distance did so by ship – there were no railways in the North Island and only 74km of railway track on the South Island. Alex’s grandparents, John Fraser and Mary Kempt were early European settlers at Waikopou Bay, near Man ‘O War Bay, Waiheke island. Alex’s parents, Peter Migan and Catherine Fraser raisied 13 children on their farm at the head of Te Matuku Bay on Waiheke. In pre-European times Te Matuku Bay was an important food gathering and canoe landing place for Maori living in the coastal settlements and nearby mountain pa of Maunganui. Te Matuku Bay was also Waiheke’s earliest European settlement but all that remains now are the sites of the first school and the Pioneer Cemetery at the head of the bay. Alex’s father, Peter Migan was instrumental in establishing this school (his children constituted a lot of the students!) and in 1866 he was the first person buried in the Te Matuku Pioneer Cemetery. Alex’s mother Catherine was also buried at the Pioneer cemetery in 1916 as was his sister Kate in 1931. The entire Te Matuku Bay area was declared a marine Reserve in 2003. Ngati Paoa Maori are tangata whenua and traditional guardians for Waiheke and Te Matuku Bay. The area is of historic, cultural and spiritual importance to the Ngati Paoa.

As a youngster Alex had some sporting ability as the following newspaper report from 1884 indicates:

Although anything in reference to this island seldom appears in your columns, it is nevertheless going ahead in a quiet way. There is now a very nice public school on the island. Saturday, the 19th April, was a gala day here for young and old. A treat (the first of its kind here) was ‘given to the district school children in the form of athletic sports and picnic, which took place in Mr. Mclntosh’s paddock. Everyone seemed to enjoy themselves and those children who ran badly at the sports made better running when the buns and cakes were distributed. Great praise is due to the teacher and committee for the manner in which they conducted the fete. The most distinguishable event of the day was the jumping with the pole by Alexander Migan, a boy under eleven years of age, who jumped 5ft. 11in. over a bar. It is the intention of the teacher and the committee to hold the children’s sports every year if possible. Great praise is gone to Mrs. McDonald, who was entrusted to choose the prizes for the children, for her very good selection. (New Zealand Herald, 2 May 1884)

At 13 years of age, after the death of his father in 1886, young Alex left school having decided on a career as a sailor. The few existing pages of his sailing memoirs can be read here. Alex first worked as the ‘boy’, earning 5 shillings per trip, on the barque ‘Nellie’ which was ‘one of the smartest cutters on the coast’ and owned by the Kauri Timber Company.

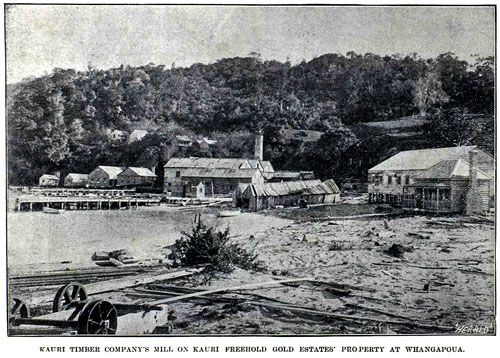

The Kauri Timber Company was a Melbourne-based syndicate which dominated the kauri felling and milling industry from 1888 onwards. Newspaper shipping information in 1886 indicates the ‘Nellie’ was engaged carrying 30,000ft of kauri timber each 100k trip from Whangapoua, on the Coromandel peninsula, to Auckland. Kauri trees did not grow at all outside the Auckland province and the kauri timber industry was a mainstay of the Auckland economy. In the late 1880′s around 42,000,000 super feet of kauri was exported by ship annually from Auckland, mainly to Melbourne and Sydney. The Melbourne market became so overstocked that kauri began to be exported from Auckland to London, Fiji and occasionally to New York.

To stand in a kauri forest surrounded on all sides by tin smooth, grey trunks of trees, the diameter of which varies from 3 feet to 12 or 15 feet, and whose symmetry is not destroyed by branch much under 80 feet, is an experience not lacking in impressiveness (Auckland Star correspondent)

It’s probable that Alex witnessed or participated in the 1890 Auckland Maritime Strike. Lined up along the wharf to prevent cargo being loaded or unloaded, striking water-siders picketed the Auckland waterfront during the strike, the country’s first big nationwide industrial dispute. Together with seafarers and miners, the wharfies were supporting their Australian counterparts, who had gone on strike for the right to form unions. The strike spread across the Tasman when a major New Zealand employer, the Union Steam Ship Company, employed strike-breakers to load its ships in Australia. The army and mounted police were used to control pickets in New Zealand’s main ports. The largest companies in the dispute, the Union Steam Ship Company and the Westport Coal Company, worked together to smash the unions. The Seamen’s Union secretary later recalled that the unions had been ‘licked, and … also kicked and kicked very hard indeed’ (Neill Atkinson, Crew culture: New Zealand seafarers under sail and steam. Wellington: Te Papa, 2001)

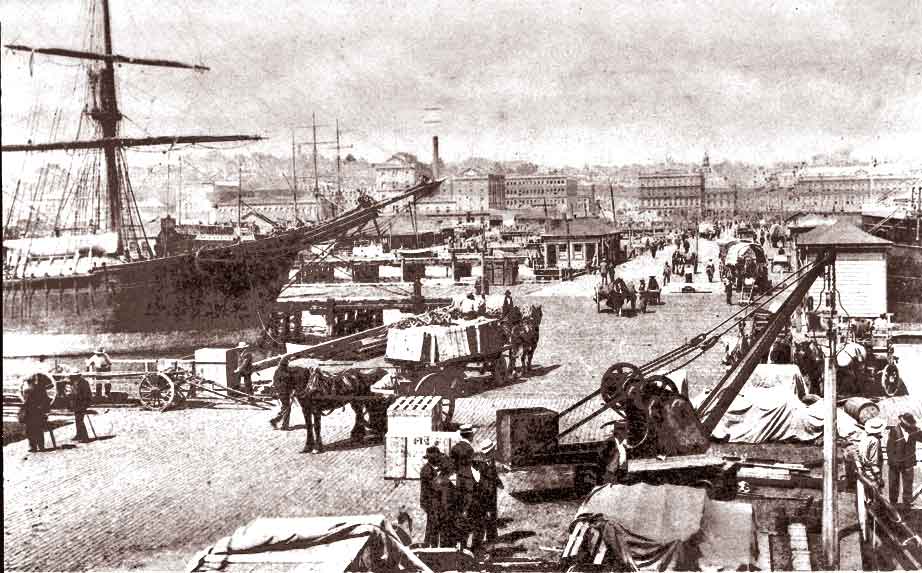

In 1894, due to an error by her master Captain Castles, the ‘Nellie’ went onto rocks between Mercury Bay and Tairua Harbour and despite attempts to re-float her, she was eventually abandoned and completely wrecked. Evidence provided to the subsequent enquiry by Mr A. Rose, Collector of Customs revealed that the ‘anchor chain got foul on the windlass’ and it was sworn that ‘There was no grog on board ; The captain was perfectly sober and there was no drinking on board, neither was there drinking at Mercury Bay”. Alex continued moving up through the seafarer ranks; from third-hand, to ordinary seaman and then able bodied seaman on various barques shipping Kauri timber from Coromandel to Auckland, Melbourne and Sydney. Queen St. wharf, would have been a very familiar place to Alex as he sailed into and out of Auckland harbour. He shook off his ‘pollywog’ status and qualified as a ‘shellback‘ on his first square rigged ship, the ‘Star Of The East’, twice taking Kauri timber to New York during the last decade of the 19th century.

The term ‘seafarer’ covers a huge variety of roles and ranks aboard ship. In the age of sail, the main sail-handling, steering and maintenance tasks were carried out by able or ordinary seamen under the supervision of the master and his executive officers (mates); other workers performed specialised duties such as carpentry, sail making and cooking. The ‘Star Of The East’ first arrived in Australia in 1889, having sailed from New York with Captain William Turner as master. Just before ‘Star Of The East’ sailed, Captain Turner resurrected an old sailing ship custom by buying a brand new bowler hat. He always wore this hat whenever he was ashore on ship’s business or when leaving or returning to the ship in port. It was a custom that he maintained to his dying day and it was this which earned him the nickname of Bowler Bill. In 1915 Captain Turner was infamously scapegoated by the British Admiralty as master of the ‘Lusitania’ when it was torpedoed and sunk by a German U-Boat with the loss of 1200 lives. The ‘Star Of The East’ also met a sad end in 1907 when she was wrecked at Axim, Gold Coast Colony (now West Ghana). Due to his negligence, her master, Captain Le Blanc had his license suspended for 6 months. Alex’s memoirs indicate he sailed on the ‘Star of The East’ under Captain Biss from about 1891 to 1893.

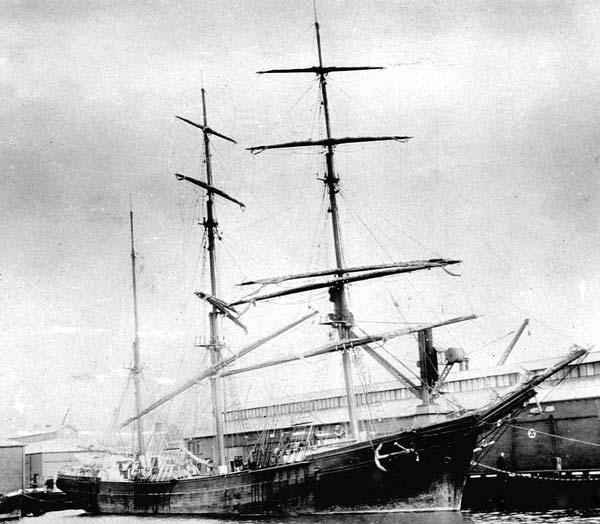

Kathleen Hilda

After the ‘Star of The East’, Alex joined the crew of the barque ‘Kathleen Hilda’, an intercolonial timber trading ship. “I joined her about the time the Kauri Timber Co’s. mills were going at full blast. And every old ship that was available at that time had no trouble in picking up a cargo for either Melbourne Sydney or Adelaide. And then to Newcastle for coals, back to Auckland. I was in the Old Kathleen Hilda for nigh on two years”. A round trip from Auckland to Melbourne, Sydney, Newcastle and return usually took about 2 1/2 months. In his memoir Alex mentions finishing his time on the ‘Kathleen Hilda’ in 1895 after a friend of his was swept overboard and died at sea. The incident was reported in the newspaper as follows:

THE KATHLEEN HILDA. MAN LOST OVERBOARD: Capt. McKenzie, of the barque Kathleen Hilda, which arrived yesterday from Newcastle, reported the loss of the second mate. It appears that on the second day out from Newcastle, November 3rd, at 10 p.m., a heavy sea which swept the deck carried overboard Mr Ellis Thomas Free, the second mate. A heavy southerly gale was blowing at the time, and a heavy sea running. The Kathleen Hilda was brought up into the wind and tacked about the spot for two hours, but no sign was seen of the unfortunate man. Free, who has been on the barque for a number of years, and is well-known here, is a single man, a native of Adelaide, and with no relatives in the colony as far as is known. (Thames Star, 14 November 1895)

Alex then looked around for work onshore and found a job refitting the barque ‘Astracarnia’ which had put into Auckland after being damaged by gales on her way from New Caledonia to Cape Town with a load of nickle ore. He declined an offer from the Captain to join the voyage to Cape Town. Instead he then went ‘up country’ for 6 months, painting a 380ft. railway bridge for the New Zealand Railways. Alex’s career as a seaman was revived as he returned to the sea working on steamships. He was employed by the Northern Steamship Company on the ‘Glenelg’, the ‘Chelmsford’, the ‘Muritai’, and ‘Waimarie’. The crews on the steamers in the early 1900s were housed in the forecastle, which was fitted out with bunks. Beneath the bunks there would be a few small lockers/drawers for belongings to be stowed. Meals were eaten at a small table and the seats were a couple of wooden benches. The officers cabins were located in the midships section, near the boiler and engines. This meant the cabins would have been hot and noisy. The master, mate, chief engineer and the cook had separate berths. The cabins were very small; the typical size was 2 x 1.5 metres, just long enough for a bunk and either a desk or set of drawers. Generally, it would have been hard work on the steamers. However, the officers and crew had a fairly relaxed time on ‘excursion’ days.

A steamer excursion and picnic had become an increasingly popular leisure activity. There would have been some preparations carried out before the excursion and carrying out of tasks such as wiping coal smuts off the deck seats. Then the crew would have been busy embarking passengers and loading excursion gear. Once at the destination and while the passengers were taking part in activities on shore, the crew relaxed by fishing and chatting. The hardest task of the day would have been counting the passengers back on board to ensure the numbers had not been exceeded and everyone was accounted for. After the excursionists had disembarked at the end of the day, the crew went back to the normal routine of loading cargo into the ship for the next voyage.

Alex was a member of the Seamen’s Union and testified in the Arbitration Court during the Seamen’s Dispute regarding the payment of overtime in 1902. Seamen worked on vessels which were either sea-going, doing what were called ‘outside runs’ or working closer to shore on Coastal Traders doing ‘inside runs’. They were only paid overtime for the ‘outside runs’. The Northern Steamship Company testified in regard to monthly wages;

“we are paying at present £6 10s for able seamen, £8 10s for firemen and greasers, £6 10s for trimmers and £4 10s for ordinary seamen. The system of watches is left to the captain. It is four hours on and four hours off. The stokehole and greaser hands keep six-hour watches”.

The union called James Dunning, manager of the Coastal Steamship Company; John Metcalfe, fireman on the ‘Wakatero’; Win. Crockett, seaman on the ‘Chelmsford’: Arthur Goodman, a fireman who had served on the ‘Gairloch’; John Vergo, who had been in the employ of the Northern Union Steamboat Company; and Alexander Migan, who had been in the service of the Northern Steamship Company. Alexander Migan said he,

“had worked on several of the Northern Steamship Company’s vessels. He considered there was room for improvement in the present conditions under which the men were working. The clause with regard to having meals between certain fixed hours could in his opinion easily be made workable”.

Mr. McGregor, from the McGregor Steamship Company, in making a case for not paying the seamen extra, stated:

“The seaman’s lot is better, he is better paid, and better looked after than the settler or the settler’s son twice over, and I speak from a knowledge of both parties.how do I come to the conclusion that the settler is having a bad time, I may say that the wool he received 5 1/2d for two years ago he is now receiving 2 1/2d for, the gumfields from which settlers have derived considerable revenue are becoming as extinct as the moa; timber is scarce, and you can buy a case of fruit in the market today for 1s, and of that the settler gets about 3d or 4d”.

John Metcalfe, fireman on the Wakatere, in answer to Mr. Belcher’s question: “How long are you on duty from the time you turn out at six a.m?” said;

“It all depends if we run straight back from the Thames. If we run from Auckland and back from the Thames, from the time, I turn out in the morning to the time I knock off at night is about 10 1/2 hours, without including any cleaning up or anything like that. My duty never ceases till the vessel gets to the Thames; and, in fact, till she comes back again. I have only time to take my meals. I kept a book for one week, which was just an ordinary week, not an excursion week, and including cleaning and general work my time for the week was 73 hours 10 minutes. That is including cleaning and work on the boilers after we got in. Taking the double trips with the single trips you cannot make the average less than 10 hours per day. You must, do a certain amount of cleaning. The 73 hours 10 minutes includes all the work I did for the week. It is in my wife’s handwriting, written at my dictation, at the time. My wage is £8 10s”. Mr.Belcher; ”You remarked that you would not go back to the Northern Company’s service again. What is your reason?” “Because I was not treated properly, having to work 12 hours. I think the work warrants an increase of wages”.

Alex. Migan, A.B., employed by the Northern Steamship Company in the ‘S.S. Glenelg’, ‘S.S. Chelmsford’, ‘S.S. Muritai’, ‘S.S. Rosamond’ and ‘S.S. Waimarie’, examined by Mr. Belcher, said:

“In the Chelmsford and Muritai I have done what is known as inside running. The number of hours worked by men on deck in the inside running by my experience is 10 to 12 hours a day on the Chelmsford. That includes working cargo and working the ship. I do not remember any occasion working under eight hours. I consider the special clause just and fair. It would be an improvement on the present system. I understand the nature the articles I have signed. They lay it down that I have to be there whenever called upon. The conditions under the special clause could not possibly be worse than at present. On one occasion on the Chelmsford I thought I was entitled to be paid for overtime, but I did not get it. On Christmas day 12 months ago we were down at Waiheke and did not get paid, and on New Year’s Day we went down again, stopped all day and came back picking up cargo all the way. I got neither cash payment nor time off for that.” (New Zealand Herald, 30 January 1902)

When the New Zealand Electoral Roll was taken in 1905-6, Alex is recorded as being a mariner on board the coal ship ‘S.S. Rosamond’ on the West Coast at Grey. The Rosamond seems to have been somewhat accident prone:

THE S S ROSAMOND IN COLLISION. Wellington, June 29. The steamer Rosamond, coal laden, from Greymouth, while coming alongside the wharf at midnight ran into the Brunner Company’s coal hulk, striking her amidships. The latter immediately sank. Fortunately the keepers of the hulk were ashore ready to assist in making fast to the wharf. The damage done to the Rosamond is only trifling. (Grey River Argus, 30 June 1888) 10.03.1898: Grounded at Farewell Spit.

THE S.S ROSAMOND. Again Disabled. Sept. 2, The steamer Rosamond, from Westpot to Dunedin, was towed here by the ‘Brunner’ last night, with her machinery disabled. (Star, 2 September 1893)

ACCIDENT TO S.S. ROSAMOND: Christchurch, October 26. At Lyttelton this afternoon the Rosamond, from Greymouth came into collision with the end of No. 7 wharf shortly after entering within the moles. She was going astern at the time, and though the engines were put ahead when the steamer neared the wharf, she had so much stern way on that she struck it a few feet from the south-west corner. ‘The force of the blow split one pile and dislocated the structure for nearly half its width and for a depth of three bays pr about 25 feet. The planking was torn apatt in places for distances of more than a foot, bolts were broken, rails displaced, and the whole concern thoroughly shaken. (Grey River Argus, 26 October 1900)

- 25.08.1908: Struck the wharf at Onehunga. 20.08.1910: In a collision with Kotuku at Onehunga.

- 14.02.1911: Suffered a fire while in the Cook Strait.

- 26.02.1911: Experienced damage while in the Cook Strait.

- 13.11.1911: Ran aground at Manukau.

- 14.08.1916: Struck the wharf while docking at Napier.

It is not known how they met but on 24 November, 1908, Alexander married Olive Grace Quennell in Melbourne. He had travelled over on the Union Company’s steamer SS Moeraki (and was probably working on it at the time!) which sailed from Wellington on November 10th, had an extremely rough voyage across the Tasman to Hobart and then berthed in Melbourne on November 21st.

Alex with ?his best man onboard SS Moeraki. Going from Auckland to his wedding in Melbourne, 1908

Their marriage certificate indicates the wedding was not at a church, but at 19 Camberwell Rd, Hawthorn; which is the same address Alex was staying at in Melbourne. Olive (commonly called ‘Dolly’) is noted to be a dressmaker while Alex occupation is given as ‘mariner’. Their witnesses are Olive’s father William Quennell and one Walter Fraser.There is a note on the marriage certificate from the cleric that Olive signed with her new married name instead of her maiden name. It is not known to me where, or if they honeymooned but the S.S. Moeraki left Melbourne for the return trip to Wellington via Hobart again on 27 November. Perhaps Alex took his new bride back to New Zealand to meet the Migan family?

Alex presumably would have gotten on well with his father-in-law as both were Union men; indeed William had been secretary of the Victorian Operative Bricklayers Society for many years. Alex and Dolly’s first child, Alexander Bruce, was born in Auckland, New Zealand on 29 October, 1909.

As Alex is recorded as residing at 24 Pompellier Terrace, Auckland in 1910 (NZ Directories), I presume that Alex and Dolly lived their early married life in Auckland, while Alex continued work as a seaman on the steamboats. Their second child, my grandmother, Thelma Mary, was born in Hawthorn, Melbourne on 30 May 1912.

The following information from the Australian Electoral Rolls indicate where the Migans lived and also that Alex continued working at sea until he was over 50 years of age:

- 1906 and 1911 electoral rolls indicate Alex was working on board steamers

- 1914 10 John St, Hawthorn, Victoria. Occupation: Stevedore

- 1919 14 Wattle Grove, Hawthorn, Victoria, Australia. Occupation: Mariner

- 1924 Cnr Camberwell Rd & Smith Rd, Camberwell, Victoria, Australia Occupation: Seaman

- 1942 7 Small St, Hampton, Victoria, Australia Occupation: Painter

- 1949 7 Small St, Hampton, Victoria, Australia Occupation: Painter

- 1954 7 Small St, Hampton, Victoria, Australia Occupation: Painter

Dolly, Thelma and Alex at Small St

14 Wattle Grove, Hawthorn is immediately across the road from 7 Wattle Grove which was the home of Dolly’s parents, William Thomas & Mary Quennell. Dolly lived there as a youngster. Some years ago, by a miraculous co-incidence, my mother, who needed to move back into Melbourne for the work she was doing at the time, rented her own grandparents’ former home at 7 Wattle Grove, Hawthorn.

Alexander died, aged 80, on July 16 1954 at a private hospital in Sandringham, Victoria. Dolly survived Alex by a little over one year. She had been living at Victoria Grove, Ferny Creek and on September 28 1955, she died at Ferntree Gully Hospital, Victoria, aged 72 years.

My mum remembers little of her grandfather, except to say that he was a quiet, taciturn fellow who never spoke of his life, his ships or his homeland. But she has an abiding memory of Alex George Migan at Hampton, sitting by the waters edge and staring out to sea.

Hi. I am somewhat of a secret in the family. Having always wondered where I came from this website has been amazing. I have been able to obtain so much information and share it with my children who are so excited to hear about their ancestry. Thank you so much

Hi I am Terry Migan son of Alexander Bruce Migan and Dawn Isobel Migan .I have a brother Peter Migan and a sister Diane Migan who is now Diane Parker. Thelma Migan was my aunty.

What a great site you have here.I thought I would be called up for national Service In Vietnam so joined Royal Australian Air Force and served in Australia in a Bomber Squadron for 6 years Canberra Bombers, Phantom F4E fighter Bombers, as an electrical technician and then did 2 years training on F111’s and got out when my 6 years was up.Cheers Terry

Great to hear from you Terry – I’ve sent you an email